|

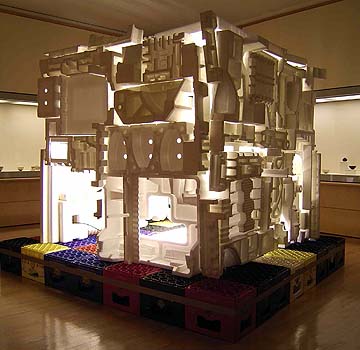

Yoshiaki Kaihatsu - An Employee of the ADF Corporation

catalog “Happo Yoshiaki Kaihatsu” Museum fuer Ostasiatische Kunst Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Germany, 2005 |

|

|

|

| Photo (c) Gianni Plescia |

|

The decisive beginning of Yoshiaki Kaihatsu’s artistic career was his 1992 solo exhibition “Series: No Brain is functioning any longer - Part 1” at the Natsuka Gallery in Tokyo. For this exhibition Kaihatsu founded the company “ADF (Art Development Farm)” - a fictional company that produces art. Kaihatsu hired himself for this company. This step is in itself not surprising, because after all this is the normal career path of young Japanese men, who go to work as diligent employees and whose everyday lives are filled with blind dedication to the company’s assignments. At this time Kaihatsu also began to wear only gray clothing in his everyday life. This clothing suggested the uninterrupted function of the employee and his ready willingness to work. For his first exhibition as the company ADF he installed a round, rotating ceiling in the gallery space, from which headphones hung down, and through these headphones the name of the company was incessantly repeated and the noise of moving trains could be heard. Visitors were able to wear the headphones, but then they were forced to walk along with the turning ceiling. Their view of the advertising posters on the walls was also controlled with the same precision as the acoustics - a situation that bordered on brainwashing. In the following years Kaihatsu realized two further exhibitions at the same gallery under the same title. In 1993 he took up the calm world of small children, which suffering employees (“salarymen”) apparently long for. Before the central train station in Tokyo he walked into the crowds of gray-clothed salarymen during rush hour wearing an oversized baby costume, thus dramatizing their regressive desire. In 1994 lockers were installed in the exhibition space with a large image of a waving, gray - clothed employee. Graves of brainwashed salarymen, lost to themselves and on the verge of committing suicide. Since this time Kaihatsu has become a complete workaholic, both in his public and private life. Gray is a color between black and white. It is “in between” two polar conditions and thus belongs neither to one nor the other. The “salarymen,” who spend their lives fulfilling tasks as company employees, are neither “white collar” (office employees in white shirts) nor “blue collar” (workers in blue work clothes). Salarymen actually wear white shirts, yet because of their function as cog-wheels in the firm’s operations they can also be understood as “blue collar” workers. Based on their unclear role, but surely also because their clothes are frequently gray, salarymen are called “gray collar” workers in Japan. And these “gray collar” workers actually constitute a particularly broad class in Japanese society, upon which the Japanese economy is based. As intermediaries they willingly take care of the tasks assigned to them. Kaihatsu, who similarly wears gray clothes and is responsible for the production of art, directs his attention to the invisible things in everyday life and “blindly” works to make them visible. Up until now these things have included dust picked up from various different locations (his studio, an empty apartment house, a closed down school, or the surroundings of a nuclear power plant), pages from pornographic magazines, ex-girlfriends, memories of the existence of things, or undocumentable concepts like “love” and “thanks.” Or also the bullet holes preserved in the facades of houses in Berlin as well as the Styrofoam material he picked up there. They all became Kaihatsu’s raw material, which he transformed into art, and through his efforts they acquired the power to make statements. When one attempts to express the direction of Kaihatsu’s attention, perception, and interest more concretely, one encounters the concept that one has already become acquainted with as the title of one of his works: “vanity.” Kaihatsu employs the word “vanity” to describe things that sometimes disappear or can no longer be perceived. Where is the boundary between these “vanities” and the things that appear clear and important around us? Won’t all of the things in our currently existing world eventually transform into “vanities”? This notion coincides with the Buddhist theorem “everything is ku” (literally “emptiness,” which means an unqualified emptiness that represents the basis of all forms of appearance). This world view, which may seem hopeless and sad at first glance, has allowed the diligent and responsible Kaihatsu to flourish happily and magnificently on the stage of the international art world, while he himself busily works in the background in his inconspicuous gray uniform. English translation: Anthony Enns |

| - - - - TOP - - - - Copyright ERI KAWAMURA 2013 all rights reserved. |